Charles Lindsay-Fynn considers the unnatural reasoning behind a clean, humane kill.

On the bullet striking the animal, it buckles on impact and labours out of sight into the tree line before you can take a second shot. It is sickening, gut-wrenching, a bad shot; your fault. It’s not a case of if it will die, as the wound is mortal, but when. How much suffering will the deer undergo?

In today’s society, with hunting being a controversial and divisive topic, it is inevitable that there are many conversations being had on the ethics of hunting and the principle of the humane kill. It is the goal of modern conservation hunters to ensure the deer is killed as quickly and cleanly as possible, ideally with a single shot. As the reader is likely already aware, head and neck shots can achieve this if successfully placed, but the most common and widely accepted target is the chest cavity, where the heart and lungs are located. A clean kill does not necessarily mean the animal will drop on the spot; in most cases an animal dispatched with a well-placed cavity shot will still run a short distance before coming to its final rest. In these cases, the deer is still dead upon impact, with the bullet tearing through the heart and lungs, but the brain just does not know it.

Above: The Perfect point of aim

Hunters go to great lengths to ensure a clean kill. They follow government legislation on legal calibre and bullet design. Time is spent down the range ensuring their scope is correctly zeroed and their handling of the rifle is well practised. Uncertain shots are not taken and investments are made in high performance equipment such as appropriate clothing and optics. They will often have educated themselves through qualifications such as County Deer Stalking’s’ Proficient Deer Stalker 1 (PDS1) or the British Deer Society’s Deer Stalking Certificate. All of this requires a large commitment in both time and money, and yes; one could argue that this is all done to improve the chances of a successful hunt, but a clean kill is inextricably linked with the hunter’s success.

However, for a hunt to be successful, many elements still need to come together, and it can take just one of these to go wrong to lead to poor shot placement. The scope can get knocked whilst crossing a fence, the bullet deflected by an errant twig, the deer moving at the last second, a gust of wind, or just plain human error, to name but a few. When as little as six inches can be the difference between a clean kill and a wounded animal, there is little margin for error. On top of all these risks, the hunter always has in the back of their mind, an awareness of how badly it can go wrong, adding pressure to the shot.

It is important to remember that we lay down these high standards for ourselves as hunters.

We alone have set the clean kill as a benchmark for hunting and not just an ideal to strive for. If that animal were to die in any other way, including by natural causes, in nearly all cases, it would be a far more prolonged and painful death than by a hunter’s bullet, even when shot placement is not perfect.

Perhaps, with the UK countryside being fairly tame and lacking any apex predators capable of tackling deer, except man, we have forgotten how brutal nature can be. The vast majority of deer in the UK die either to a hunter or an automobile (approximately 74,000 road traffic accidents involving deer occurred in the UK last year). Concerning the latter, in many cases these will not be instantly fatal to the deer, leaving them to experience a slow death or to carry debilitating injuries for the rest of their lives. In dispatching a deer, the hunter holds themselves and is held to, a frankly unnaturally high standard.

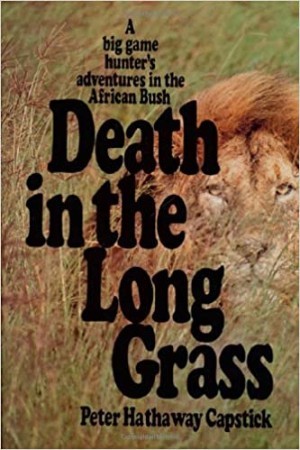

To remind the reader of the realities of nature, here is a short extract from Death in the Long Grass, by professional hunter and raconteur Peter Hathway Capstick. Here, he recalls a particular rhino that lived alone and near his hunting camp on the Munyamadzi River in Zambia. The rhino seemed indifferent to the presence of humans and became the unofficial mascot of the camp, affectionately known as Ralph:

To remind the reader of the realities of nature, here is a short extract from Death in the Long Grass, by professional hunter and raconteur Peter Hathway Capstick. Here, he recalls a particular rhino that lived alone and near his hunting camp on the Munyamadzi River in Zambia. The rhino seemed indifferent to the presence of humans and became the unofficial mascot of the camp, affectionately known as Ralph:

‘One day, driving by, I pulled the Rover over in surprise. Ralph stood by the side of the road looking like he had been recycled. His front horn was half ripped off and hung over his nose like a nightcap, his flanks and legs tatters of flesh. Obviously, he was in terrible pain and dying. From his rear end hung a large piece of intestine, ripped free by a pack of hyenas… He has apparently tangled with another bull Rhino, or for all I know, an elephant… weakened and sick, he hadn’t been able to do much about the Hyena pack that has chewed away most of his lower rear and equipment, then left him still alive. Africa has little compassion in such matters’.

The word ‘Africa’ in the last sentence could easily be replaced with ‘Nature’.

As a conservation hunter, one takes the principle of a humane dispatch as a basic standard, but why is that so? There are perhaps three main and overlapping rationales for this. Firstly, there is the material reason of carcass preservation. If the guts are damaged by the shot, this will increase the risk of the meat being contaminated. Similarly, if the deer is able to run a fair distance before expiring and the carcass cannot be found for some time, meat will spoil if not gralloched and become tainted by the blood. Using the deer as a source of food and returning all usable parts to the food chain is an important element of hunting, which is best achieved through a clean kill.

Secondly, there may be an underlying element of guilt that comes with having to perform deer management, which is somewhat mitigated through making the kill as clean as possible. In Britain, all of the deer’s natural predators (except man) have been exterminated via hunting and destruction of habitat, with the last wolf being shot in 1680. As a result, human involvement in the management of deer numbers is essential in maintaining a healthy deer population. For proof one only has to look at the case of Barons Down in North Devon, a deer ‘sanctuary’ run by the 'League Against Cruel Sport' where they refused to allow any deer to be culled (exposed in 2002). This in turn led to dozens of deer dying of starvation and disease as their population outstripped the carrying capacity of their habitat.

A guiding principle of responsible deer management is the humane dispatch of the animal. It is only logical that with the increasing need for human intervention, there is a need for increased responsibility towards the welfare of the deer. If we accept the fact that man must step in to rebalance nature, taking the place of the bear, lynx and wolf, then those actions should be conducted as humanely as possible, with every effort made to avoid the prolonged suffering of the deer.

Finally, there is an unreserved love and respect for deer as a species. These mysterious and secretive animals, that wander at will through the forests, fields and hills of the British countryside, have a definite air of majesty. One could not try to gate keep the appreciation of these animals to hunters alone and you only have to go as far as London’s Richmond Park to see all manner of people hoping for a sighting of the deer who inhabit it as proof. Who, but a true sadist, would ever want to see them suffer? Certainly, one of the most confusing elements of hunting for many to come to terms with is if you love an animal, why would you wish to kill it? But conservation hunters admire the species and the idea of deer, more than the individual animal; and for the species to thrive it must be managed. From hunting these animals, one can learn more about them than someone with no field experience. This in turn develops a level of respect and appreciation that someone with a removed perspective would have. The culmination of a successful hunt is the kill and in this action a conservation hunter can only wish for it to be as quick and clean as possible.

A recent article by PETA claims that 11% of deer stalked in the UK ‘died only after being shot two or more times and that some wounded deer suffered for more than 15 minutes before dying, though they gave no actual source to these claims. Here they are using this statistic to try and demonise hunters to the public and shame them for their actions, as if a wounded deer was a desired result. As this article has hopefully shown, they could not be further from the truth. Instead of PETA’s message, one should consider what Steve Rinella, renowned American Hunter, author and conservationist calls the ‘the arena of consequence. He describes how if you live a life close to nature and hunt within it, the experience you have out there, whether it be on a cultivated farmers field in the home counties or out on the rugged hills in Scotland, come home with you in a complex cocktail of emotions and memories. Perhaps there will be an occasion when you kill a deer but not as well as you should have. All you can do is sift through the mix of whatever lessons you can draw from the experience, and be better prepared, both mentally and physically, for the next hunt.

If you'd like to read more about perfect shot placement simply follow this link: shot-placement-on-deer

Alternatively, perhaps you'd like some training? In which case the PDS1 Certificate is the perfect place to start and will take you through the best practice for acheiving the perfect shot and recovering shot animals, along with a host of other relevant information and techniques.

To read about the PDS1 cource click here: proficient-stalker Or call 0203 981 0159 or email